History of Aberdeen Mills

The history of Aberdeen Mills goes back further than the birth of the United States – and in reality much further back than that. Once inhabited by only Native Americans, the move into this area by Europeans mostly, required cooperation or if nothing else tolerance for each other’s presence. In fact, as you will soon read this was a requirement to settle this land!

I am including here an article, in its entirety – as far as I know – written sometime in the 1950s. The author uses terms that people today know are not appropriate in referencing various people’s cultures and I too agree. I would like to share this article as it was written as a historical record of not only what he reports as the history of this property but also as an example of how people needed to change – and even now some still need to change – the language that is often used in order to show proper respect to all cultures. Thank you for taking the time to read this before we get to the interesting history of Aberdeen Mills as written in the following article.

A Historic Writing of Aberdeen Mills

A BRIEF HISTORY OF ABERDEEN MILLS

By H. E. REEM

Written in 1953

Ofttimes the inhabitants of a particular community journey many miles to view some point of interest that may have historical prominence and is therefore appealing to the public, and forget places of interest in their own community.

During the year 1774, an elaborate building program was started at what is now known as Aberdeen Mills, located along the Conewago creek about three miles north of the borough of Elizabethtown. Here, 179 years ago, (written 1953) was erected a large grist mill in a remote section. Then an area that was inhabited by very few white people. The red man, or Indian, (Native Americans) roamed the forests and surroundings in the quest of the food animals, fish and birds that were abundant.

Prior to starting the construction of this mill, the owners of the land obtained a direct grant from the Penns which required a peaceful settlement, or rather had to gain the friendship of the red man (Native Americans).

As one views this particular industry today, the question naturally arises: Why did our forefathers journey into the wilderness to establish places of industry? If one takes time to study the natural advantages of this particular point, the answer to this question is not difficult. The natural power forces to operate this mill were a great factor in the selection of this particular site. At this point the Conewago Creek flows between elevated points, and within less than a half mile has a drop in elevation sufficiently large to afford an ample supply of water to flow by gravity to operate the mill. Merely by the erection of the dam across the creek and the building of a race that was fed from the stream, the required power was supplied.

The structure originally was three-story, built of brown sandstone. As one views the walls today, it will be noticed that many of these stones are massive and cut to exact shapes and sizes. One realizes readily that there was an unusual amount of manual labor necessary to complete a structure like this. Besides the mill proper, two large 2 ½ – story dwelling houses were also erected and are of like material. Where these stones were secured we of today cannot tell. The closest areas where brown sandstone are minded is in the vicinity of Hummelstown. If secured from there, it was necessary to transport the material from the quarries on wagons as this was the only means of transportation during the period this grist mill was erected.

In addition to the grinding of the grain, which was by the huge stone process then in vogue everywhere, a distillery was also built adjacent to the mill where the surplus products of the grain were used to manufacture liquor. During the early years when our forefathers started forging their way into the wilderness and opening new territory, one of the first industries to be established generally was a grist mill. If any surplus grain was foreseen between harvests, the distillery was operated and the surplus used to make the beverage that was a common item in almost every household. The business at this particular point became one of real profit, and was followed by the construction of a sawmill and cooper works where the barrels and kegs were manufactured generally from the butt end of white oak logs. The balance of the trees were cut into different sizes and lengths of timber and sold for building purposes.

The product of this distillery soon became widely known and the farmers for many miles distant brought their wheat, rye, barley, corn and buckwheat to this mill to be converted into wheat and rye flour, cornmeal, and buckwheat flour to make griddle cakes to satisfy the ravenous appetites of the sturdy backwoodsmen. A certain amount of grain was taken in exchange for the grinding, and generally after the family supply of food was laid by, the balance of the grain was traded for several kegs or barrels of good corn whiskey or rye or barley rum.

This mill continued operations for a period of practically one hundred years without interruption save on one or two occasions. On one occasion, when the Ruckseckers (now Redseckers) had possession of the mill, a man by the name of Shearer purchased the land on the east side of the Conewago extending about one mile above and below the mill property. Some controversy arose as to who legally owned the stream; since no amicable agreement could be determined, Mr. Shearer employed a force of men to change the course of the stream, and had a channel dug through his land which diverted the course, thus shutting off the supply of water that operated the grist mill, sawmill, cooper shop and distillery.

In order to overcome this piece of trickery, the Ruckseckers promptly erected another dam across the creek several hundred feet above the one that was drained by the Shearer channel. They also extended the race line to the new dam, after which operations were again started and continued with only brief shutdowns until about fifty years ago (1900) when fire destroyed a large portion of this place of activity. The third floor was damaged beyond repair, and the stone walls were therefore lowered to the height they are today.

Some years after the second dam was erected an unusual flood almost completely demolished the dam and also partially closed the channel built by the Shearers. A new site for the more convenient and better dam was selected and constructed across the stream from where the present structure now stands. The last dam required an expenditure of much money, really more than the owners were able to finance without making considerable loans, which resulted in a heavy financial burden, and consequently a higher charge was made for grinding grain. This extra charge was resented by many of the patrons and finally terminated in the construction of the grist mills in different areas thus taking away much of the trade which seriously affected the Rucksucker mill.

Mr. George Redsecker who resided on Cottage Avenue of this borough is one of the Ruckseckers and during his boyhood days spent much time with his grandparents on this present day historic spot.

He relates an interesting method of estimating the number of bushels of corn contained in a certain field area. The method used then may seem antiquated today, but nevertheless during those early days the individual who was at the head of any business venture very rarely made an error in his calculations. Ofttimes farmers decided to sell their entire crop of corn “on the field”. To determine the amount of bushels, the purchases usually counted the rows of corn, then counted the number of stalks in a row, and finally counted the number of grains on a number of the ears selected from the different parts of the field. A measure, usually a half peck, was then filled and the number of ears determined the necessary to make a bushel of shelled corn. This was an ancient custom but was usually accepted by both the seller and the purchaser as a fair method of dealing.

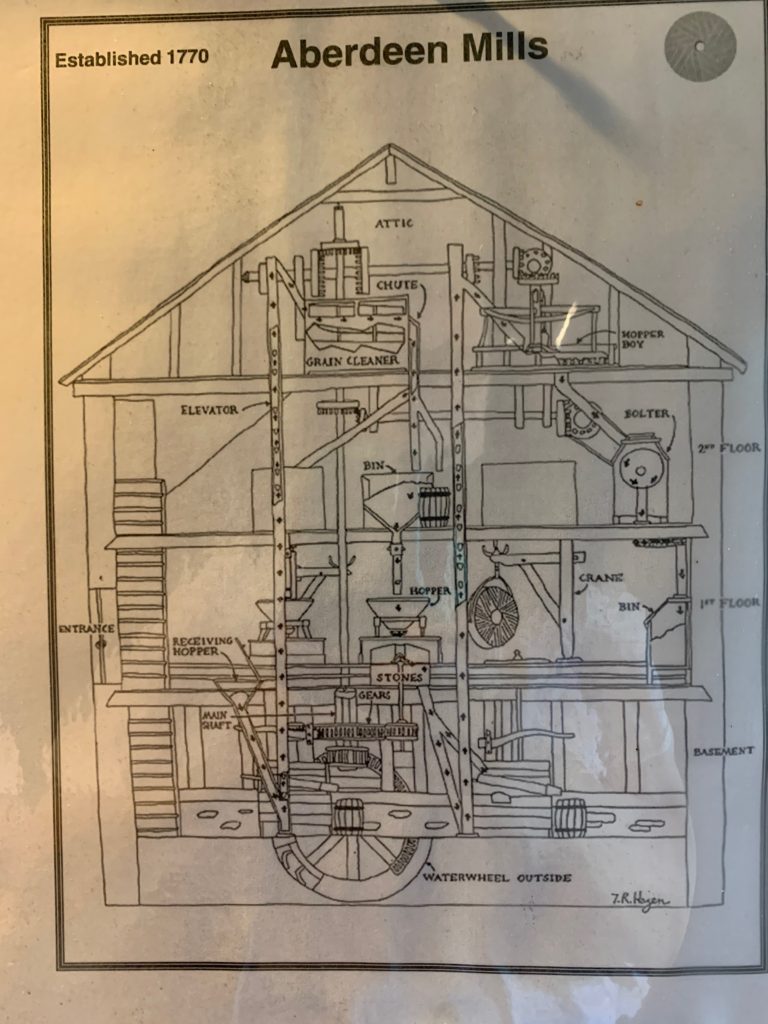

The machinery of the original grinding equipment of this old mill, excepting the grinding stones, of course, was of wood. The wheels that operated the mill were all wooden. The master wheel was about eight feet high and the gears or teeth, 12 or more inches long, which meshed a smaller wheel that was attached to the main, or master, shaft which was also attached to the huge water wheel furnishing the motive power. The speed was regulated by the amount of water allowed to flow through the chute to the master wheel.

The labor necessary to prepare these huge grinding stones was really a difficult and accurate piece of work. Those who were schooled in the profession of milling as well as the caring for the dressing the huge stones to properly grind the different grains into the proper products could command a good wage and were continually in demand. This really was an art that few persons of today can duplicate.

Some years ago Mr. Ressler came into possession of this historic mill, the old method of grinding was replaced by more modern machinery, and the grinding of grain for flour was the leading feature.

The ownership changed several times during the recent years and today, with modern equipment, the products have become known for many miles. In order to cater to the trade, the present owners are compelled to operate to capacity to fill the orders that are continually on the books. In addition to grinding grains for various purposes, the present owners also manufacture several products in the cereal family.

A few hundred yards north of the mill you will find two immense rocks located along the hillside adjacent to the dam. These rockers are termed by some as “Twin Rocks”, “Swinging Rocks” and “Pulpit Rocks”. They are about equalin size, the top of each has foot space sufficient for at lease fifty persons to stand. They rest on what may be termed a small pivotal rock and not so many years ago several persons standing on the top of the extreme southern edge could rock these huge boulders.

There is another legend to the effect that previous to the white man’s entering this territory, the Indian chiefs would use these rocks as a place to offer their sacrifices to the “Sun God” and legend has the story that several lives of Indians have been sacrificed on these rocks to the gods they worshipped.

Close by, north of the residential stone house, can be found a few tombstones. This was an established burial ground where the inhabitants within a reasonable distance interred those of families. This burial plot is overgrown with poison ivy, blackberry bushes and various scrub trees usually found in deserted areas.

“I have been researching the history of grist mills for over 10 years having acquired with my wife this amazing set of buildings situated on 40 acres of strikingly beautiful property. When we purchased the property, I had no real idea what a grist mill was. Now, 11 years into it, I have a complete appreciation for the Millwright who designed, built, and repaired the mill, the Millstone Dresser who sharpened stones as they became dull due to use, and the Miller who milled grain into flour, an essential staple of life going back thousands of years.

Mills are arguably one of the first continuous systems or machine that fully operated without intervention (with frequent maintenance). Major innovations in the late 1700’s including bucket elevator systems and better distribution of water power energy to equipment throughout the mill allowed for great expansion. It was during this period of innovation that Ulrich Scherr’s Scherr’s Mills (1774), George Washington’s Mt Vernon (1771) and Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello (rebuilt in 1803) were constructed and operated.” – Merritt